| Currency exchange |

$1 = 1.1 Euro Craic: Lively conversation

Mini-dictionary

Hooker: A small sail boat

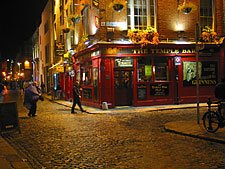

Photos

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On October 4, 2002, I started a two week trip through the west coast of Ireland and Dublin. The photos to the left illustrate places and experiences written about below.

My trip to Ireland started off with an easy flight from Londonís Stansted airport. Ryanair, the cheap airline sort of like Southwest in the U.S., has a flight that goes right to the County Kerry airport, about 30 miles east of Dingle in Farranfore. I couldnít be happier. When I started planning this trip I assumed Iíd have to fly into Shannon or Cork, neither of which I wanted to do. Both were cities and this would be my very first experience driving on the left. City traffic wasnít exactly the trial by fire I was looking for.

Thankfully, Kerry was remote and I had no trouble getting the hang of left side driving in that setting. The Kerry airport was really nothing more than a landing strip and a single small building. The main part of the airport seemed to be only the baggage carousel and a small counter for two customs agents. When I was there I didnít realize the agents were from customs. I just grabbed my bag off the carousel and headed for the exit door on the right. One of the agents stepped in front of me to stop me. I didnít know how to react. I hadnít heard any stories of customs in Ireland being all that onerous. The bigger of the two started asking me questions, "Where are you coming from?" I answered "London Stansted". As he asked a couple more questions, he must have noticed my bewilderment and realized I wasnít a smuggler or a terrorist, just a confused tourist who wasnít expecting a bag inspection. He closed my bag, pointed me to the door, and wished me a good day.

Once through the door, I saw to one side three or four small booths. These were the Ďofficesí of different rental car operators. To the left was a customer service counter with several passengers in line, but no one there to help them. One lady, whose fine clothing and jewelry seemed incongruous with a budget airlineís clientele, was becoming visibly agitated and started speaking to no one in particular how she thought it was ridiculous that she had to wait and that she expected better service than this. Being impetuous as I am, I was halfway tempted to remind her that she had just flown in on Ryanair. If she expected first class sevice, maybe she shouldnít fly a budget airline.

I had pre-arranged a rental from Hertz, so I got in line waiting my turn. I had heard before I left that my American Express wouldnít provide the CDW insurance in Ireland as they normally would. Mastercard is the only credit card that still provides CDW coverage. So, I took the careful step of getting confirmation in writing from Mastercard that they would cover the CDW and presented it to the Hertz agent at the counter. A lot of good that did, since they required a minimum of $1500 in available credit, which I didnít have. I ended up having to take the expensive insurance provided by Hertz, doubling the cost of my rental. Oh, well.

I stopped in the airportís sizable cafeteria for lunch, which was actually a full Irish breakfast. Iím not accustomed to so much meat and fat, so I was a bit apprehensive at first, but I have to say, it was an excellent meal and filled me up for the rest of the day. After lunch, I made my way outside, first to the cash machine, since I had no currency, and then found my little rental car. And I do mean little. It was a Fiat Seicento, about the smallest car on the road in Europe. I was amuzed by the sticker I saw when I first climbed in. Over the steering wheel on the dashboard was a reminder, "Drive on the left." I guess theyíve had enough rental cars come back worse than they went out, with drivers who explained, "I forgot..."

I set off right away and didnít have any trouble getting myself used to driving on the left. It helped that the gear selection and foot pedals operated just the same as in the U.S. The biggest adjustment was figuring out which way to look for oncoming traffic. It would seem logical just to look in the opposite direction from what Iím used to, but the brain doesnít work like that. After so many years, driving becomes instinctual. You canít rationalize with the brain to all of a sudden behave in ways opposite of what itís been trained to do. Coming to an intersection is confusing and inherently nerve-wracking.

My second concern was making sure I wasnít getting lost. I had a good map with me, but trying to drive and read a map at the same time seemed a bit dangerous to me, and the roads didnít seem to match exactly with the map anyway. Somehow, I did manage to stay on the right road and was making my way closer to my destination, the town of Dingle. On the way there, I knew I wanted to stop by the beach at Inch. I thought, how odd that thereís a beach like this in Ireland. I was under the preconceived notion that Ireland was just green rolling hills, plenty of sheep, and not much more. Although the weather was a bit cool and windy, the beach at Inch could easily be a scene from the Atlantic shores of North Carolina. Not quite what Iíd pictured as my introduction to Ireland.

As I kept driving, I noticed the landscape becoming progressively more rural. The road narrowed and I started seeing sheep grazing along the roadside, something that is almost a trademark of this area. As I kept driving, I kept telling myself that my destination had to be just around the corner. Finally, I saw a village just over the horizon and knew that it had to be Dingle. Before going into town, I checked into my hostel, the Ballintaggart. Itís a huge farmhouse full of character, complete with cows grazing in the field out front.

Dingle is a fun and friendly little town. The main street is lined with colorful houses that make me think Iím in a real life version of the game Candyland. From the top of the hill looking down, I can see the beautiful green hills that surround the area. The people here are lively and gregarious and thereís always a good time to be had in one of the many pubs here.

The Irish are known for being welcoming and hospitable. I found that to be mostly true, but not without some effort on my part. If you go and donít find a warm reception right away, take the initiative to strike up a conversation. You wonít be rebuffed and sharing in conversation with one of the locals will be one of the most memorble parts of your trip.When I first walked into some pubs it seemed like people were looking at me like I had green skin and horns.

In the off season, youíre not likely to see many tourists, and the locals arenít expecting visitors either. However, once I found a seat and ordered a Guiness, I found the pubs to be pretty comfortable. Dingle probably has the highest ratio of pubs to people of any town in Ireland, with only 1000 residents and 50 pubs. Probably the best known and most jovial are An Droiehead Beag, right on the corner of the main road downtown, and Dick Mack, a little further up the road and around the corner.

Dick Mack is quite a curiosity. Itís a hardware store by day and a pub at night, and barely bigger than a walk in closet. The walls are lined with tools and farm supplies, almost as if this were some art nouveau decorating scheme from a chic New York nightclub. But once youíre here you realize itís more utilitarian than asthetic. I had to make a real effort to navigate my way to the bar. I felt a bit claustraphobic at first, having my usual zone of personal space diminished to nothing. Despite itís tiny size and smoke thick enough to choke a firefighter, Dick Mack is a favorite with visitors, incuding several celebrities. The sidewalk outside is Dingleís own little walk of fame, with concrete squares commemorating visits from Dolly Parton and Julia Roberts, among others.

Down the road is An Droiehead Beag, undoubtedly the best pub in Dingle for traditional Irish music, called simply Ďtradí for short. The music here starts nightly at 9:30 and is supposed to last until about midnight. However, while I was here, the music was still going until nearly 1 a.m.

The pub is divided into roughly three different compartments that cater to a different crowd in each. In the back and to the left is a room for the rowdier crowd with a bar of itís own and some pool tables along the back wall. On the other side itís a bit quieter, and several couples gather around a cozier semicircular bar and the tables in the corner. In front is where the music plays and the crowd here is attentive to the talented performers. Typically, youíll find three or four musicians here playing the guitar, violin, flute, and bohdran. Soon after the music starts, the front room fills up quickly.

The pub feels warm and inviting, with dark wood and many nooks perfectly suited to small groups and close conversation. Everyone in the room seems to be smiling and having a good time. The walls are covered with nostalgic signs and haberdashery. The room is friendly and comfortable. I feel at home here instanstly. Soon after I entered I found myself chatting with a couple of friendly Irish girls who were visiting Dingle for the weekend. I came to find thatís not uncommon. Dingle is a popular weekend getaway for people from all parts of Ireland.

The Dingle Penninsula is one of the most rugged and remote areas of Ireland. In this area youíll find stacked stone walls laboriously built centuries ago, narrow roads, green mountains, and grazing sheep. Itís the quintessential Ireland you see pictured in travel guides. On my second day here I set out to see it for myself. I headed west toward Slea Head. My plan was to make a day of it and loop around to Ballyferriter before heading back to Dingle.

My first stop on this day trip was the very tip of the penninsula, Slea Head. This rocky area of the coastline was the setting of the film Ryanís Daughter, which set off a wave of tourism to this area. Thereís even a stone monument commemorating the film at the spot where most of the filming took place.

Sparsely populated and utterly scenic, the tranquility here was everything I had hoped for. In the distance are the uninhabited Blasket Islands. The few remaining inhabitants on the islands were ordered by the Irish government to move to the mainland in 1953. Curiously, about 80% of them emigrated to the United States instead, settling mainly in Springfield, Massachusetts. The Blaskets are now a popular day trip for hikers and ferries run out to Great Blasket, the largest of the five islands, fom Slea Head several times a day.

There is a small beach at Slea Head. Even though my visit was in October and I expected the weather to be cold, itís actually pretty warm and sunny. The water is warm enough for a swim. I was in no hurry and I couldnít think of a more perfect way to start off my relaxing vacation than frolicking in the water.

Most of the Dingle Penninsula is whatís known as the Galtacht, the last remaining areas where Gaelic is spoken as a first language. You see this more the further you go west of Dingle town. At the very end of the penninsula are the tiny towns of Dunquin, which boasts the westernmost pub in Ireland, and Ballyferriter, where I found a little cafe where I stopped for lunch after touring around Slea Head. At this cafe, I listened in fascination as the barmaid seamlessly switched back and forth between English and Gaelic, depending on her customer. Most of the customers around the bar appeared to be locals. Most of them were chatting in Gaelic.

Apart from the language, it seems this little area is almost a separate nation from Ireland that speaks itís own language and lives by itís own rules. One glaring example of this was witnessing a boy who looked no older than 10 sharing a beer with his dad.

On my second day in the area, I went to the north side of the penninsula, over the narrow mountain road called Connor Pass. The scenery along this route was unlike anything Iíd seen yet in my trip to Ireland. As I drove farther out of town, it almost felt like I was entering no manís land. I had the road to myself. The road soon became steeper, the landscape rocky, and the road filled with more sheep who seemed completely oblivious to my car. The feeling of isolation was striking. I could almost picture myself in an episode of The Twilight Zone.

The clean mountain air was exhilarating, and all the way to the top I still didnít see any other cars or people, something I wouldnít see until I got to the obsevation deck at the top.

At the top, I take a break and get out to see the sights. It seems as if you can see for 20 or 30 miles from here. There is a 360 degree view here and itís a great place to take in the beauty of the many lakes and mountains that make up this area. Just up the road, there is a tranquil little waterfall and stacked boulders that just beg for me to go climbing. I was also eager to get up close to a sheep that was relaxing on a ledge looking down at me. He didnít appear to be alarmed at my presence and I decided to see how long he would remain still. I didnít see him move, but when I got to where he was laying, he was gone. I guess he was only pretending to be unconcerned.

The drive up from Dingle had been uneventful since I had the road to myself, but as I started on my way downhill, I realized it wasnít going to be that easier. This side had gotten quite narrow and was more winding with some blind curves that gave me pause as I approached. Just as I was thinking about how dangerous this stretch of road was, I was met by another car heading right toward me at a speed far too fast to be safe. I suppose it had to be someone used to driving this road, because he didnít even try to slow down, but somehow managed to miss me with only inches to spare. Though the other driver was long gone, I shared a few words with him that arenít fit for print. I was a bit rattled to say the least, and contemplated whether I should continue down this side. I kept going though. I had been told of a windsurfing competition in Castlegregory and thatís where I was headed.

Once I made it down the hill, I was on my way to Castlegregory. Enroute, I passed by an enormous beach at Kilcummin, where another surfing get together was taking place. But Castlegregory was where the real excitement was this day. The International Windsurfing championship was being held at Brandon Bay, with the biggest celebrities of the sport scheduled to be here.

When I arrived at Castlegregory, the scene looked like Woodstock at the beach, compete with VW vans. Many people had piled into cramped cars and parked randomly along the dunes, wherever there might be space. The sand dunes, sun, and the breeze all took me by surprise. That this could be Ireland just didnít register with me. It seemed so contrary to what I had expected. This seemed more like Florida. Wind and water sports are very popular here. All over the place I see people have arrived with kayaks strapped to their car. Several sailkites are on the long beach.

I made my way to the alcove where the competition was to be held, at Brandon Bay. This looked a little like MTVís spring break. A modified Jeep was blaring music and an autograph booth was set up across from that. Primary colors seemed to be the theme with a lot of bright blues, reds, and yellows.

Although I didnít know who they were at the time, I saw Diony Guadagnino, Bjorn Dunkerbeck, and Nik Baker, three of the top windsurfers in the world. Dunkerbeck is the three-time world champ. I was also approached by Jamie Knox, who I came to find out is one of the biggest promoters in Ireland of windsurfing gear and competitions. He noticed me taking notes and must have assumed I was a journalist. He was a large and imposing man, with a bald head and a booming baritone voice. His interest waned as soon as he realized I wasnít a journalist and wouldnít be able to give him any publicity.

Unfortunately, after hanging out on the beach all day (there are worse ways to spend a day), that dayís competition was called off due to a lack of wind. Ireland was having a real Indian summer and as the promoter put it, "no one expected Brandon Bay to have no wind in October."

I decided to head back to Dingle, but not before exploring some of the remote areas around the north side of the penninsula. I really didnít know which way I was heading, but I followed a road that indicated I was moving toward Brandon mountain. On the way, I passed through Stradbally and the pastoral little town of Cloughane, which almost seemed deserted.

I never made it to Brandon mountain. Somehow I got diverted north to Brandon point, a quaint little gathering place overlooking the bay. This is one of the most remote corners of Ireland, but here I found an oasis of sorts. There was a sizable gathering here around the small harbor. Kids and dads were side by side on the pier with their fishing poles. The bayside restaurant was doing brisk business with tourists who were lingering over their Guinness. I imagine they were guarding their ringside seats to what would be a beautiful sunset.

I decided I wanted to get back to Dingle before that though. I didnít want to be on the Conner Pass after dark. As it turns out, Iím glad I got back to Dingle early. I went out with my camera to the harbor and captured a photo that turned out to be one of my best ever.

After dark, I still had some film to finish off. I wandered around for a while to see if anything might make an interesting night shot. Soon after that, for the second night in a row, one of the local school sports teams came in a caravan through town, hanging out of their cars and honking their horns. I made a guess that thatís their ritual when they win a game.

I finished up the night in Murphyís pub, just off the harbor. I took a seat at the bar next to an American lady and her daughter, who seemed to be quietly arguing over the daughterís decision to drop out of school and become a bartender. The mother, oblivious to the bartender in front of her, raised her voice and said, "youíll never amount to anything by being a bartender."

On my right, a guy in his mid-twenties took a seat. To strike up a conversation, I asked if he knew what the caravan from earlier was about. As it turned out, he was only visiting here from London. He had intended to stay for just a couple of days, but had been here for a week already. He introduced himself as Neal, and we became fast friends for the evening. Over too many pints, our discussion ranged from travel to politics and almost everything in between. The night ended up being a pub crawl. Our next stop was Dick Mack and then on to what had become my favorite Dingle pub, An Droiehead Beag.

I picked a bad night to overindulge. I was planning to be up early the next morning to head off for Doolin, on the central west coast in County Clare.

For the first time on this trip the weather started turning a little bit ugly as I was approaching Doolin. I first had to make a stop at the impressive Cliffs of Moher. The cliffs themselves almost seem to appear out of nowhere. As you drive into the park, the ocean is quite a ways in the distance and the cliffs form into a mound just before dropping off 700 feet to the water below. Itís not until you view the cliffs from their profile do you see this dramatic drop. The long walk from the parking lot to the edge is a flat plain, deceptively flat. All of a sudden you cross through the gate and the precipitous drop is revealed.

The Cliffs of Moher are immense and imposing. Thereís no way to escape the realization that if you stand too close to the edge, one strong gust of wind might send you to the bottom in a hurry. Like most people, I saw the sign that said "Danger. Do not cross this point" and, like most people, dismissively ignored it. The only way to really appreciate the cliffs is to get up close and experience the thrill of their impending danger. Whether or not youíre a religious person, standing - or more likely laying prostrate on your stomach - at what seems like the edge of the earth canít help but give you a sense of reverence for the majesty of this awe-inspiring planet.

Soon after I arrived at the cliffs, I saw the first rain during my trip. I wouldnít get the gorgeous sunset photo of the cliffs that I came here for, but thatís OK. I got a couple that Iím happy with and, more importantly, I got to spend some time at this reverent place that Iíd become so familiar with through words and pictures.

From the cliffs, I made my way a few miles up the road to Doolin and the Aille River hostel. Maybe it was the drizzling weather, the hangover, or the long drive, but Doolin disappointed me a bit. Iíd read about how this tiny little town was all the rage among Europeans. People fly in for the weekend to obscure little Doolin from Paris and Berlin. Maybe so, but I fail to see why. I will say, Gus OíConnerís pub had some character, and the music was good, as was the Guinness and seafood. But during my stay here, I couldnít help but think that Doolin would have been better suited to a few hoursí stopover in a daytrip. Spending a night here, I felt, was limiting my time in other places Iíd rather have been.

I will have to say though that after a few hours here my outlook improved. At the hostel, I introduced myself to some fellow travelers who arrived shortly after I did. Graciously, they offered to share some wine and cheese they had brought with them, just the kind of hospitality I was badly in need of at this point in my tirp.

After a couple of hours of fun conversation and some more wine and cheese by the fireplace, we all decided to wander down to hear some good music at OíConnerís. Joe and Lisa, Nacho and Charlotte and I sat in for a night of good Ďtradí. Without exception, the music in western Ireland is excellent. Thatís one thing you can count on when you come here.

The music this night was no exception. The musicians start off with rousing, uptempo tunes, usually including guitar, fiddle, tin whistle, bodhran, and occasionally accordian. Almost every Irish song has a witty and ironic story behind it, and the humor is usually specific to the Irish experience, so if you donít Ďget ití, donít worry about it. Just enjoy.

As is typical in a trad session, sometime soon after eveyone is in a good, jovial mood, the musicians start a lament; a sad, soulful song telling Irelandís historical tales of sorrow, loss, struggle, strife, famine, or poverty. This may sound depressing, but in actuality, itís a reverent moment that evokes a mood of appreciation for the resiliency of the Irish people and a thankfulness that the bad times are in the past. In a way, itís a stirring reminder of what good-spirited people the Irish are, that despite being ever mindful of the suffering theyíve endured, they are mostly cheerful, hardy, and gregarious people in spite of it all.

The lament doesnít last but for one song and the musicians are back to the lively reparte and the sprightly songs that brings out the cheery side of tonightís audience.

This goes on until shortly after half-eleven (or eleven thirty to Americans). Joe and Lisa left before this to catch up on their sleep. Nacho, Charlotte and I lingered a bit, still enthralled with lively music here, and set off to return to our hostel. On the way back, all three of us, almost simultaneously, noticed how still, slient, and peaceful our walk in the cool night air was. We were walking under the new moon, so we were surrounded by the near complete blackness of night. Except for the stars, which seemed brighter than usual without having to otherwise compete with the moon to light up the night, we were barely able to see each other or the road.

The absense of light, strangely, was both unsettling but so tranquil at the same time to the three of us, so used to the ubiquitous light present in cities. For me, it took me back years, to my childhood in rural Ohio, where my neighborhood friends and I had about 20 acres between our houses to roam and trails that we plowed connecting them all.

Itís moments like this that remind me why I love traveling so much. It really takes me back to nature, refocuses my priorities, and seems to present me with some kind of epiphany on life every time.

After my time in Doolin, I made my way on the road toward Galway, stopping in Kinvara for lunch. Kinvara is a pretty little town with not much to see except a few brightly colored buildings along the harbor and Dunguire castle, which usually looks more impressive in pictures than it did in person. Itís sort of a hollow shell of a castle now. On top of that, when I arrived the water level was low, so the pretty lake Iíd seen in photos was now a marshy bog. Coupled with a grey sky, I realized I wouldnít be getting any prize winning photo of this site.

So after lunch I moved on. From doing some reading beforehand, I thought I might like to stop and see the Ailwee Caves, a wide open cavern on the edge of the Burren. When I spotted the signs, I followed along and stopped in, but after getting there and seeing that I had to wait for a guided tour, and that there was a significant entrance fee, I decided this is something I was going to have to skip. Later, I would realize what a good decision that was.

I continued along and was now headed to Rossaveal, the port where I would catch the ferry to the Aran Islands.

This 30 miles stretch of road on the west side of Galway was my first glimpse of how empty and open Ireland can be. It was mostly flat with almost steppe-like grass, an occasional puddle of water - nothing that could be called a lake, or even a pond - gave some variation to the features of the land. As desolate as the land here was, I found it also to be calming and beautiful in a way that I wasnít accustomed to.

As I arrived at the port in Rossaveal, I then realized what a fortuitous decision it was to skip the Ailwee caves. I had been a little lax in my planning for this part of the trip. I really didnít have any idea of the ferry schedules, only that there were three a day between this port and the Aran islands in the off-season, such as it was during my October visit. I had arrived five minutes before the 1:30 departure. The next one didnít leave for another four hours. And there is precious little - as in nothing - to keep oneself occupied or to kill time at this ferry landing other than watching fishermen at work.

On the 45 minute ferry ride, I got my first taste of Irish autumn weather. I was standing on deck with a jacket, scarf, and cap on and was still tempted to go below deck to get warm. Of course, it really wasnít that cold, but with a lingering mist in the air, what the Irish call Ďsoft rainí, and the speed of the boat going about 20 knots, it made for a chilly experience. But I stayed on top, fascinated by the view of those Aran islands Iíd read so much about coming closer and closer into view. I could see the three islands, dotted one by one next to each other. The larger Inishmor seemingly dominating compared to the two smaller islands, Inisheer and Inishmaan. They seems a lot closer than they actually were, I suppose because I could see them soon after we left the ferry port.

When we finally pulled into the harbor at the main town of Kilronan on Inishmor, I was happy to see the hostel I planned to stay at, the creatively named "Kilronan Hostel" was right there, painted unmissable yellow. The bad news, as I came to soon find out, was that despite reassurances over the phone that I wouldnít need to make a reservation in October, there were no rooms available here, and no one on hand to inquire about it. There was simply a closed door and a sign printed on a piece of paper, "No rooms tonight". That was a lesson learned.

So instead of the cheap hostel room I had expected to stay in, I had to go way over budget and stay at the one room I could find. It was at a B&B called the "Dormer" just next to the grocery store, behind the main square. The proprietor was a very kind lady who gave me a break on the price, thirty euros instead of the usual forty, I guess half because she sympathized with me and half because I was her only guest that night. Her other twenty or so rooms were stark empty.

This was a lot more than Iíd planned to spend on any one night. This was a budget backpack trip after all. But after settling in there and realizing how quiet it was and how I might get a really good nightís sleep, it didnít seem such an unreasonable premium to pay. In fact it was probably a very serendipitous indulgence and much needed at this point in my trip.

The night before at the Aille River hostel in Doolin, the accommodations were in a shared dorm room, typical of hostels. One of the other people in the room had a snore so persistent and obnoxious that they should have never been permitted to stay in a common room. I tried to ignore it for most of the night, but finally at 3 am, the thought that I had earplugs in the car was too tempting. I got up, fished around for my keys in the dark and went out to get the earplugs. After that, I got maybe another four hours of decent sleep. As much as I enjoy staying in hostels, snorers can really be a major downside. Thankfully, Iíve not found them to be too common.

The next day, I woke up fully refreshed and went downstairs to enjoy a full Irish breakfast that was prepared for me and me alone. I felt bad about the cook being called in when I was the only guest in the whole place. It seemed that this level of service wasnít warranted in light of my cut rate 30 euro stay. Nonetheless, it did me good. I was going to have a long and strenuous day.

After breakfast, I strolled down to the bicycle shop at the end of the ferry pier to rent a bike for the day. For ten euros a day, itís not a bad way to get around, especially on a scenic island like this. I took off heading to the road that goes down the middle of the island. It starts off with a steep hill that ultimately leads to a fort (name?) at the highest point on the island. To the west side of this crest lies Dun Aengus, the prehistoric semi-circle fort that sits precariously on the southwest cliffs of the island.

I was both impressed and a bit surprised at how solitary my trip out to Dun Aengus was. In the entire 5km or so I peddled, I only came across one other person, and from the camera around his neck, he appeared to be another traveler. But for that one other person, I could have easily persuaded myself that the island was empty and that Iíd been the lone survivor in some Apocalyptic catastrophe.

I did see other signs of life though, including a very friendly and curious horse behind one of the many stacked stone fences, and a couple of homes here and there. Other than that, this land is nearly deserted, almost eerily so. And the vast plains of plate-like limestone is unlike anything Iíve seen before. It was kilometer after kilometer of small stones mixed in with a very sparse amount of grass here and there. Being so utterly deserted, barren, and rocky, it struck me as being almost like the surface of the moon.

After taking my time cycling through the fascinating landscape, I finally arrived at Dun Aengus in the late afternoon. If I was surprised to find almost no one on the road here, I was even more surprised to find not a single other person once I got to the fort. I had the entire place to myself. This was very unexpected but at the same time, very enjoyable. It became almost a spiritual experience, to have the solitude and quietness, only the sound of the ocean below, to myself. No chatter from tourists, no one with a camera calling their relatives into a photo, no inane comments from people who come to places like this not knowing anything about it. Just silence, and serenity. It was something I was really needing at that point, and it really did me some good. It was the closest thing to meditation Iíd had in a long while.

I had underestimated how long it would take to bike out there, so I arrived later than I expected, and likewise, it was later than Iíd planned when I left. In fact it was so late that it was starting to get dark. By the time I got back down to the gates (itís been made into a park with an entrance station), the lone staffer had closed and locked the gate, turned out the lights, and gone home. Apparently he either forgot I was up there or, more likely, didnít care that I hadnít come back in time.

On the way back to town, I decided to take the lower road that ran along the coast. This was the first time I got the impression that the residents of the Aran Islands may not be so keen on visitors. I passed two men chatting and although they noticed me, and quite noticeably stared as I passed, they kept chatting to themselves and didnít acknowledge me, although I waved. Another person I passed, also on bike, was even more deliberately cold. As I passed I waved, he did not return my wave, but grumbled something I couldnít understand, in Gaelic, Iím sure.

Although those incidents were a little off-putting, and I almost donít want to report on them for fear of sounding like Iím complaining or criticizing, I can sort of understand it if they donít exactly welcome visitors. They are a very solitary people within a sect of solitary people, Gaelic speakers who live on an island thatís trying its best to maintain an old-fashioned life and shun the influence of nearby modern Galway. The residents here are mostly poor subsistence farmers and fishermen. They have a slow and low key life. Itís quite obvious theyíre averse to change. Necessarily, most are less than hospitable to outsiders.

But then there are some who are open and warm, like the lady who runs the guesthouse Iím staying at, and the elderly fisherman I met the morning I was leaving the island.

If ever I could kick myself for not taking a picture I should have taken, it would be a picture of this old man. He was the quintessential old Irish fisherman, complete with deeply crevassed leather-like skin brought on by many, many years of too much sun, blown by the cold, salty winds of the north Atlantic. As would be expected, he wore the Aran sweater. Itís a traditional garment of Aran Islanders, made up of distinctive patterns, long used to indicate which family he belonged to. According to the legend, entirely believeable, the identifying pattern was employed so that when a fisherman went overboard and washed up on shore, his sweater would reveal whoís family was to be notified.

His sweater was an off-white turtleneck. Over that he wore a black wool peacoat and a wool tobogon cap, rolled up. As I was standing near the harbor, finishing off a roll of film and playing with a couple of friendly cats, he approached and said in his extremely thick Irish accent, "It looks like you have some friends." The fact that heíd initiated a convesation came as a pleasant surprise, since that was the first Iíd really had anyone speak to me on the island, except when I was a paying customer of some sort. I replied, "Yeah, I think theyíre my buddies." At that, he sort of cocked his head, squinted and said a mere, "Eh?" I knew then that the dialect was going to be a challenge. He was in fact speaking English, but I was doing well to understand about one in five words.

From his clothing, I assumed he was a fisherman and opened that line of conversation. He took right to it. I struggled to understand him as he explained how to read the waves rolling in, the tides, the foam on the water, and the clouds in the skies. I feared sounding patronizing as I shook my head in, trying to indicate an understanding that mostly wasnít there. I was hoping he didnít take that to as my being superficial, because I really was enjoying the conversation and found the manís knowledge and experience fascinating.

He asked me where I was from. I replied, "From the StatesÖ" Everyone there seems to call the United States simple "the States", so thatís what I went with. "From Nashville, Tennessee." He repeated in his thick accent, "Ten-o-say?" I was a bit surprised at this bit of acknowledgement and asked, "Do you know Tennessee?" He closed his eyes as he answered, shaking his head, "No, Iíve never been anywhere." And by that, Iím pretty sure he meant heís never been off the Aran Islands.